Photography’s Long Battle for Artistic Legitimacy

Photography was born not in studios of painters but in laboratories. The medium’s first practitioners were chemists, astronomers, inventors, and entrepreneurs, tinkering with glass plates and light-sensitive chemicals.

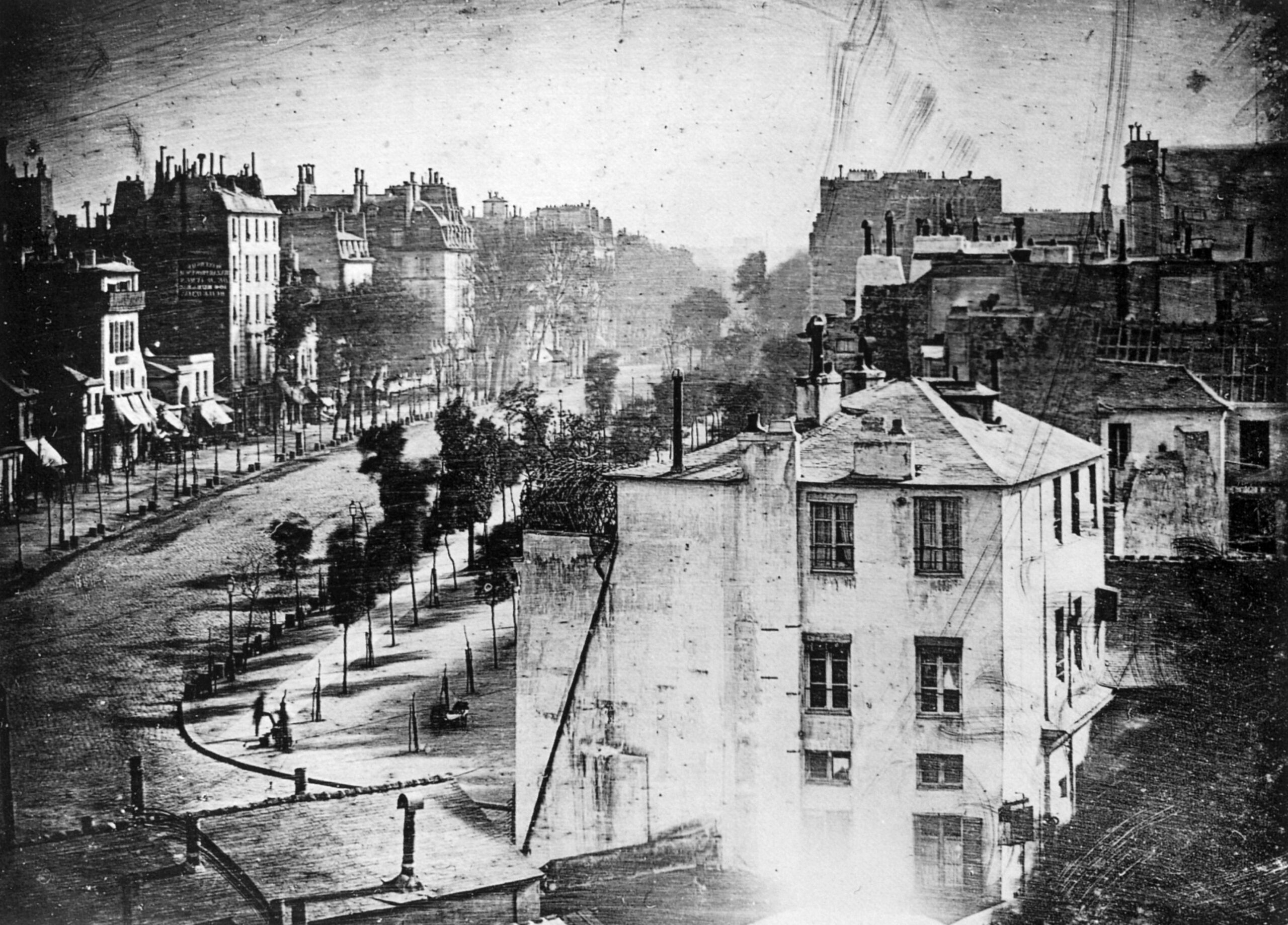

In January of 1839, Parisians crowded into the Académie des Sciences to see Louis Daguerre unveil his invention. On a silvered plate, a street appeared in crisp detail: buildings, lampposts, the cobblestones of the Boulevard du Temple. Only one man stood still long enough to register—his boots shined by a street polisher. The crowd gasped. Here was no sketch, no engraving, no brushstroke. This was the world, frozen by light itself.

From the very beginning, photography carried a paradox. It astonished as a scientific marvel while confounding notions of art. Painters had always left their mark: a visible hand, a flourish of style, the labor of craft. The camera seemed to erase that. An image fixed by chemistry and optics—could that ever be called art? For much of the 19th century, the answer was an uneasy no.

A Machine in the Studio

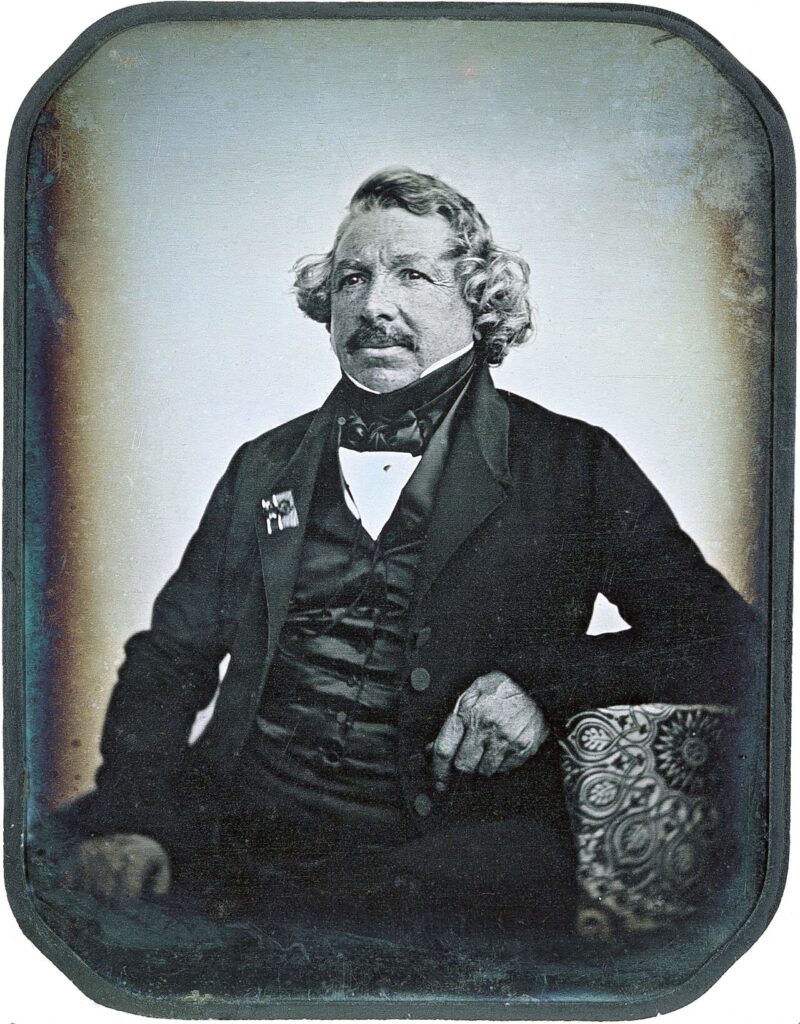

The camera’s earliest operators were not “artists” in the conventional sense but inventors and tinkerers. Daguerre himself had made his name with theatrical dioramas, illusions of shifting light and painted scenery. Nadar, later famous for his portraits of Parisian celebrities, began as a caricaturist and balloonist. The new medium attracted outsiders, polymaths, and entrepreneurs—people who straddled the border between spectacle and science.

Their images astonished precisely because they did what no hand could do. Samuel F. B. Morse marveled at the daguerreotype’s “exquisite minuteness.” Every brick, every hair, every vein in a leaf seemed etched with unforgiving clarity. Scientists rushed to adopt it.

Botanist Anna Atkins used cyanotypes in 1843 to catalogue British algae, creating the first photographic book. Archaeologists sent images of inscriptions across Europe. Photography was celebrated as a tool of knowledge—precise, portable, indisputable. But that very machine-like fidelity, the thing that made it invaluable to science, made it suspect as art.

The Portrait Dilemma

When the camera turned to people, the unease deepened. Painted portraits had always been negotiations—between likeness and flattery, realism and idealization. The photograph offered no such compromise. Victorian critic Elizabeth Eastlake complained that blue eyes turned watery, blond hair looked artificial, and shiny locks became thick ropes of light. Men fared little better, their rougher features captured without mercy. For sitters used to the painter’s gentle adjustments, this mechanical honesty could feel brutal. The photograph democratized likeness, but in doing so it undercut the conventions of beauty and status that portraiture had upheld for centuries. Was it art to show a face stripped bare, or simply evidence?

Pictorial Dreams

By the late 19th century, some photographers decided the only way forward was backward—toward painting. The Pictorialists transformed the photograph into something atmospheric, softened, dreamlike. Negatives were scratched, layered, or manipulated; focus was blurred; tones were deepened into sepia. Edward Steichen’s Flatiron of 1904 looks less like a city document than a moody canvas shrouded in mist. The strategy worked, at least for a while. Pictorialist images appeared in galleries and fine-art publications. They proved that photography could move in the same cultural circles as painting. But the cost was high: to be considered art, the photograph had to deny its own nature. It had to perform a disguise.

Straight Talk

Then came Alfred Stieglitz. Once sympathetic to Pictorialism, he turned against it. His idea was radical in its simplicity: let photography be photography. He printed his negatives without cropping, manipulated nothing, and embraced sharpness. His cloud studies, the famous Equivalents, stripped subject matter down to form, insisting that abstract patterns of light and shadow could carry artistic meaning. Modernists rallied behind this ethos. What had been condemned as mechanical now became a virtue. The photograph’s clarity, its immediacy, its stubborn refusal to flatter—these were not shortcomings but strengths. In this embrace of the straight print, photography finally stopped apologizing.

The Lingering Doubt

Not everyone was convinced. Even in 1946, critic Clement Greenberg argued that photography’s transparency tethered it too tightly to documentation. To him, it struggled to transcend the role of evidence. His skepticism echoed the doubts of the Victorians: if art required visible labor, could a machine-made image ever fully qualify? And yet, by mid-century, the verdict was already tilting. Museums collected Weston’s peppers, Adams’ mountains, Doisneau’s lovers caught mid-kiss. These images didn’t need painterly tricks to be moving. They proved that light itself, disciplined by the camera, could carry the weight of artistry.

Social Media Before Social Media

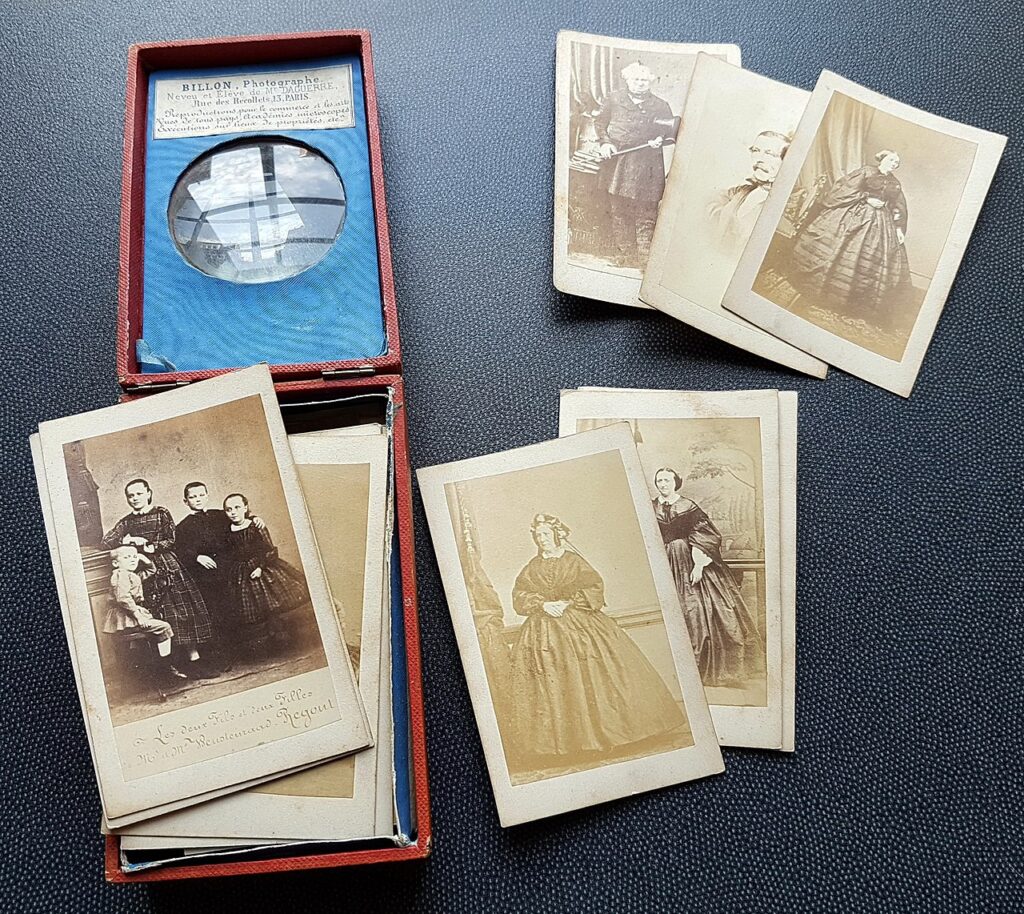

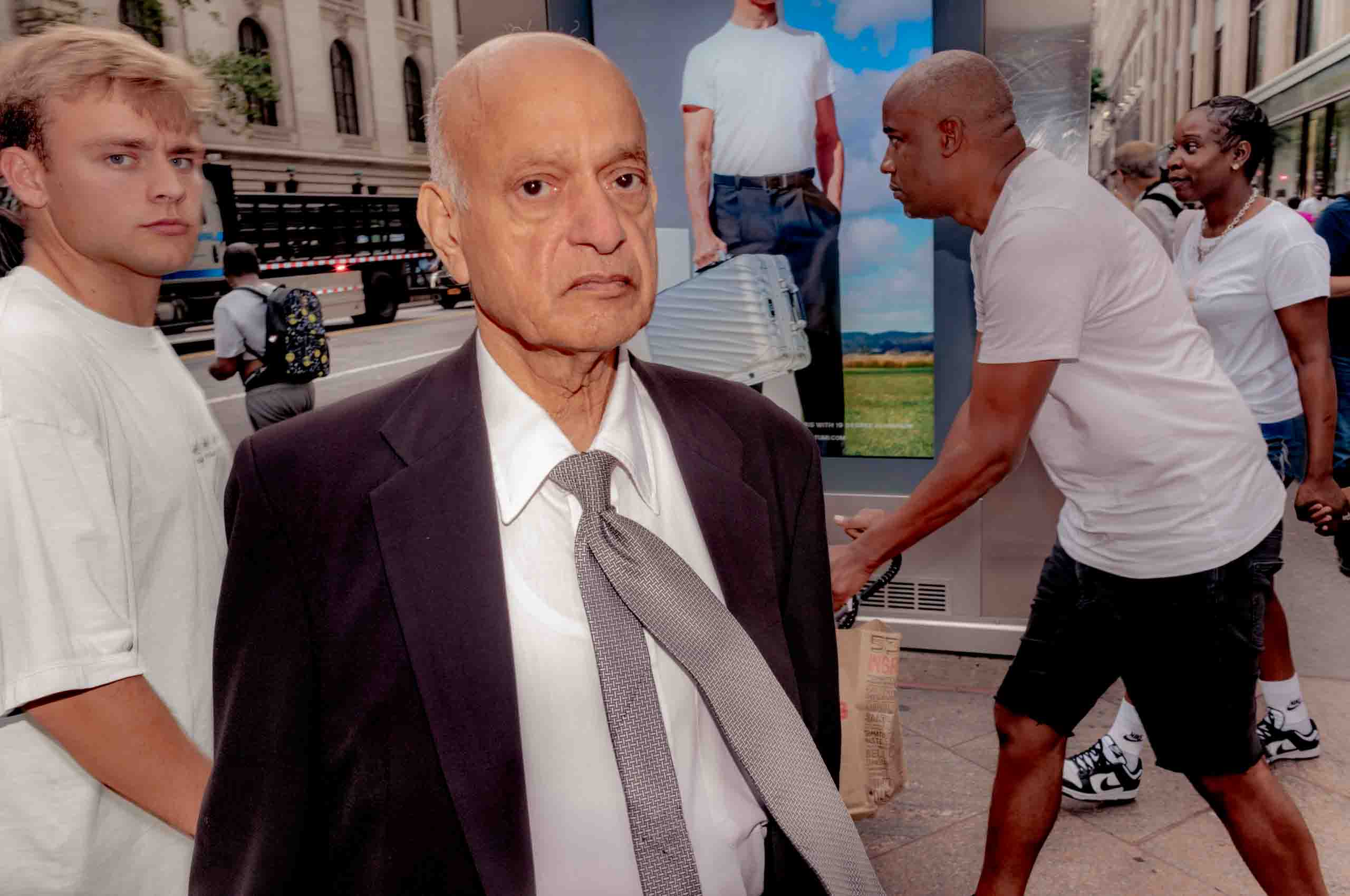

The anxieties feel familiar today. In the 1860s, small photographic calling cards—the cartes de visite—flooded parlors across Europe. People traded them, displayed them in albums, and obsessed over the latest portraits. It was, in every sense, the Instagram of its time: a flood of reproducible images, democratized and sometimes derided. Were they trivial, or cultural history in the making? The same question echoes now in debates over selfies and digital filters. Is a smartphone snapshot evidence of narcissism, or a continuation of photography’s long history of collapsing art and life? The parallels suggest that photography’s struggle for legitimacy was never simply about technique. It was about cultural anxieties over what counts as art, who gets to decide, and whether a technology that belongs to everyone can ever be taken seriously.

Light as Artist

Looking back, the arc is clear. Photography began as a scientific wonder, was dismissed as too mechanical, disguised itself as painting to win acceptance, and ultimately declared independence by embracing its own strengths. What was once seen as the machine’s flaw—the absence of the artist’s hand—became the very condition of its power. Today, Adams’ snowy peaks, Weston’s twisted peppers, and Doisneau’s stolen kiss aren’t valued because they look like paintings. They’re valued because they show us what painting could not. Photography did not become art by imitating; it became art by insisting that light itself was a creative force.

That is photography’s lasting triumph: it forced culture to admit that beauty can come not from the hand alone, but from the encounter between human intention and mechanical vision.

More Visual Culture and Theory

-

The Myth of Objectivity: How Press Photography Manufactures Reality

Reality was never the point. What we actually crave is credibility — the illusion that the world can still be known if we frame it just right.

-

Why I Reject the Pretense of Documentary Neutrality

Neutrality is a myth. Every photograph is already a construction. It’s a comforting illusion to think otherwise.

-

Double Exposure: How Kyoto and I Became Each Other’s Props

How mass tourism and social media create Baudrillard’s hyperreality.

-

Cindy Sherman’s Deepfake Ghost: Performing Identity

Cindy Sherman’s groundbreaking self-portraits expose identity as a constructed performance.