The Myth of Objectivity: How Press Photography Manufactures Reality

Reality was never the point. What we actually crave is credibility — the illusion that the world can still be known if we frame it just right.

Press photography has always sworn allegiance to “truth.” You see it in every ethics code and read it in every editorial guideline — images must be real, scenes must be unstaged, moments must be genuine in every way. The National Press Photographers Association insists on “accuracy.” Reuters warns against “manipulation.” The New York Times declares that no object or person may ever be “added, rearranged, or removed.”

I want to push back on that slightly, because I believe that the harder the industry clings to the ideal of authenticity, the more it reveals how fragile that ideal really is. Objectivity is not a virtue of the camera. It’s a story we tell ourselves to make images believable.

Press Photography and the Illusion of Intimacy

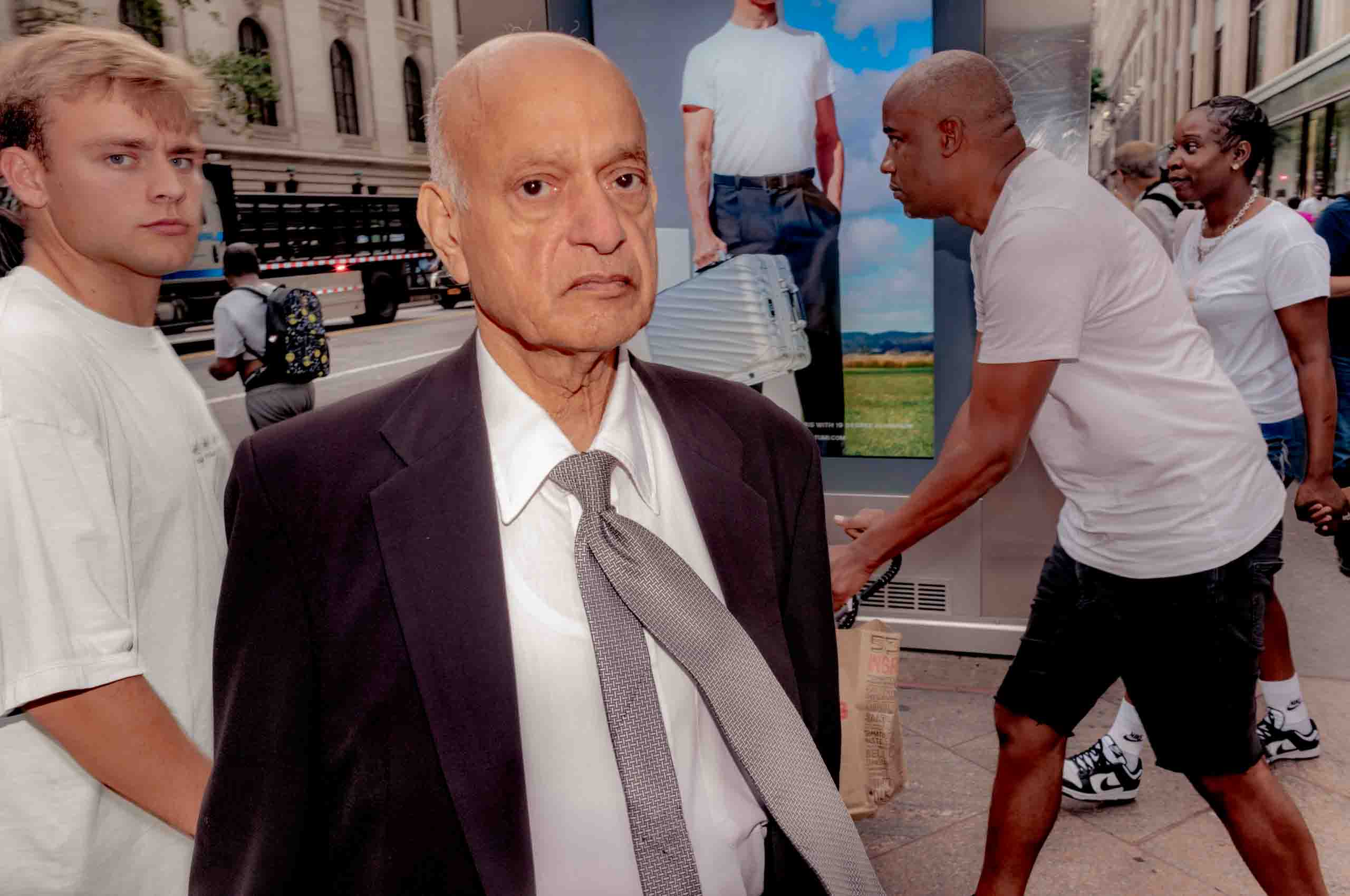

Press photography promises a kind of intimacy with the world. As if looking through a lens grants the viewer access to lives and events otherwise unknowable. But the moment the shutter clicks, the image already interprets, excludes, and rearranges reality. The frame decides what counts as visible, what is significant, what stories can be told. Even the most “honest” photograph belongs as much to the person behind the camera as to its subject. Ethical codes can insist on authenticity, but the construction of meaning is unavoidable.

The Semiotics of “Having Been There”

That construction relies on the illusion of witness. Semiotician Roland Barthes called it “having been there.” To look at a news image is to feel the drag of reality — this happened, someone saw it, now I see it too. It’s comforting, even moralizing. But photographs don’t merely witness events; they rearrange them. Barthes understood this as time’s disturbance: each image pulls the viewer backward, dissolving sequence and memory. It isn’t the past we recall but the photograph itself. The image replaces memory and becomes it.

Photographs as Architecture of Collective Memory

Visual culture academic Barbie Zelizer pushed that thought further. For Zelizer, photographs are not just souvenirs of events — they are the architecture of collective memory. When we think of disasters, protests, or celebrations, we think in images. News photographs don’t just report — they decide what the world will remember. Every claim to objectivity is also a claim to power: the power to define what counts as reality.

The Aesthetics of Suffering and the Spectacle of Authenticity

Cultural critic Susan Sontag saw something similar in the aesthetics of suffering. She noticed how certain visual tropes repeat — the body contorted, a gaze captured mid-motion, expressions rendered legible for the viewer. These conventions promise empathy but deliver spectacle. The photographer’s good intentions cannot neutralize the market’s appetite for the dramatic. What sells as authenticity often stabilizes hierarchy: the viewer as witness, the subject as evidence.

Street photographer Gary Winogrand understood this too. For Winogrand, the photograph had to be more dramatic than the thing photographed. “How do you make something beautiful even more beautiful than it already is? In the end, it has to be even more dramatic. That’s our main problem [challenge as photographers].”

Objectivity as a Social Practice

Sociologist Kevin Grayson called for a different kind of analysis — one that treats photojournalism as a social practice rather than a moral test. To understand objectivity, Grayson argued, we have to account for the lived experience of image-makers. This doesn’t just mean consideration of their identity, background, and political views. It also has to incorporate their assignments, deadlines, and institutional pressures. Objectivity isn’t an ideal to uphold; it’s a system to navigate. And that system rewards certain ways of seeing over others.

Even when images seem straightforward or transparent, they are always filtered through editorial norms, cultural expectations, and the conventions of visual storytelling. Media researcher Barbara Schneider discovered this paradox at work in her interviews with journalists. Even when reporters cared deeply about social issues, professional routines forced them to reshape their perspective into familiar storylines. Their “objectivity” was not neutrality but adaptation: a way to fit messy human experience into institutional form. The result may look truthful — but only because it conforms to collective expectations of what counts as truth.

Photography’s Power and Its Perils

Barthes warned that photography’s power is also its danger. The image convinces because it is there, but what it shows is always gone. The photograph doesn’t reveal truth; it freezes interpretation. It becomes an artifact of belief — a small monument to what a society wants to think about itself. Press images don’t just depict reality; they define it. Objectivity is less a principle than a performance. It reassures us that journalism stands outside ideology even as it manufactures one. Ethical codes, the talk of manipulation and accuracy — all of it sustains a collective fantasy that the camera can exist without a body behind it.

Cameras don’t see — people do. Every photograph, and especially those that appear in the media, is a negotiation between perception and interpretation, revelation and erasure. The question is not whether an image tells the truth. The question is more accurately, whose truth it tells (and who benefits from believing it). Reality was never the point. What we actually crave is credibility — the illusion that the world can still be known if we frame it just right.

More Visual Culture and Theory

-

Why I Reject the Pretense of Documentary Neutrality

Neutrality is a myth. Every photograph is already a construction. It’s a comforting illusion to think otherwise.

-

Double Exposure: How Kyoto and I Became Each Other’s Props

How mass tourism and social media create Baudrillard’s hyperreality.

-

Cindy Sherman’s Deepfake Ghost: Performing Identity

Cindy Sherman’s groundbreaking self-portraits expose identity as a constructed performance.