Mary Ellen Mark: The Ethics of Seeing

Mary Ellen Mark became the cartographer of intimacy within instability. Her photographs are less dispatches than allegories, balancing technical precision with an unflinching moral gaze.

Since the late 20th century, photography has not only recorded the transformations of human society but shaped how we perceive its margins. The dispossessed, the institutionalized, the celebrated, and the forgotten. If Sebastião Salgado monumentalized labor and Gordon Parks fused elegance with urgency, then Mary Ellen Mark became the cartographer of intimacy within instability. Her photographs are less dispatches than allegories, balancing technical precision with an unflinching moral gaze.

To speak of Mark is to speak of immersion. Like an anthropologist of the visible, she embedded herself in worlds others only approached on the surface. Psychiatric wards, brothels, street corners, traveling circuses.. The method was slow, insistently human. Long before she lifted her camera, she lived alongside her subjects—sharing meals, waiting through boredom, enduring suspicion or hostility. Out of this presence came trust; out of trust, images that refused the easy spectacle of suffering in favor of dignity, contradiction, and endurance.

The Architecture of Attention

Her 1979 project Ward 81 remains exemplary. For weeks she inhabited Oregon State Hospital’s women’s ward, learning its rhythms before making a single photograph. The resulting images—beds pressed against bare walls, tentative embraces, faces caught between vulnerability and defiance—carry the density of lived knowledge. One recalls Foucault’s Madness and Civilization: institutions as architectures of control, where humanity both resists and adapts. Mark’s patient method stripped away sensationalism, revealing instead what Roland Barthes once called photography’s “air”: the irreducible presence of life before the lens.

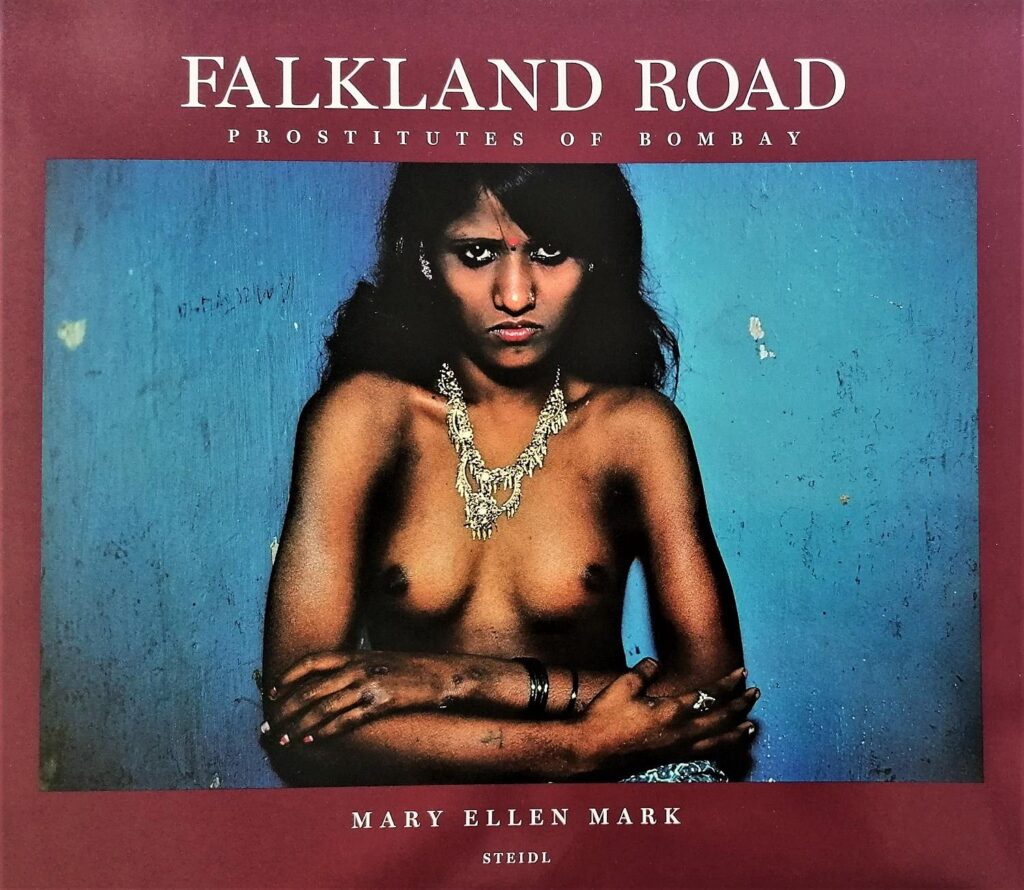

That same persistence defined Falkland Road (1981). Walking the Mumbai red-light district without a camera, enduring harassment and garbage thrown in her path, Mark carved a place for herself through repetition. When at last she photographed, the images carried the gravity of earned permission: vibrant interiors of pinks, blues, and ochres, punctured by gestures of fatigue and fleeting tenderness. Like Diane Arbus before her, Mark insisted on proximity to lives society preferred not to see—but where Arbus sought estrangement, Mark sought recognition.

Tools as Modes of Relation

Mark’s technical decisions were never neutral. They functioned as extensions of her philosophy of connection. The Leica 35mm, quiet and unobtrusive, enabled her patient street practice: pre-focusing at five, eight, fifteen feet until distances became instinctive. Medium format imposed a slower, ceremonial pace, suited to her Indian Circus portraits where performers posed as if stepping into Caravaggio’s chiaroscuro. Most radical was her embrace of the monumental 20×24 Polaroid. In series like Twins and Prom, the camera’s sheer presence demanded collaboration. Subjects saw the results instantly, collapsing the hierarchy between photographer and sitter. The image was no longer a theft but a negotiation, a shared creation.

The Human Contract

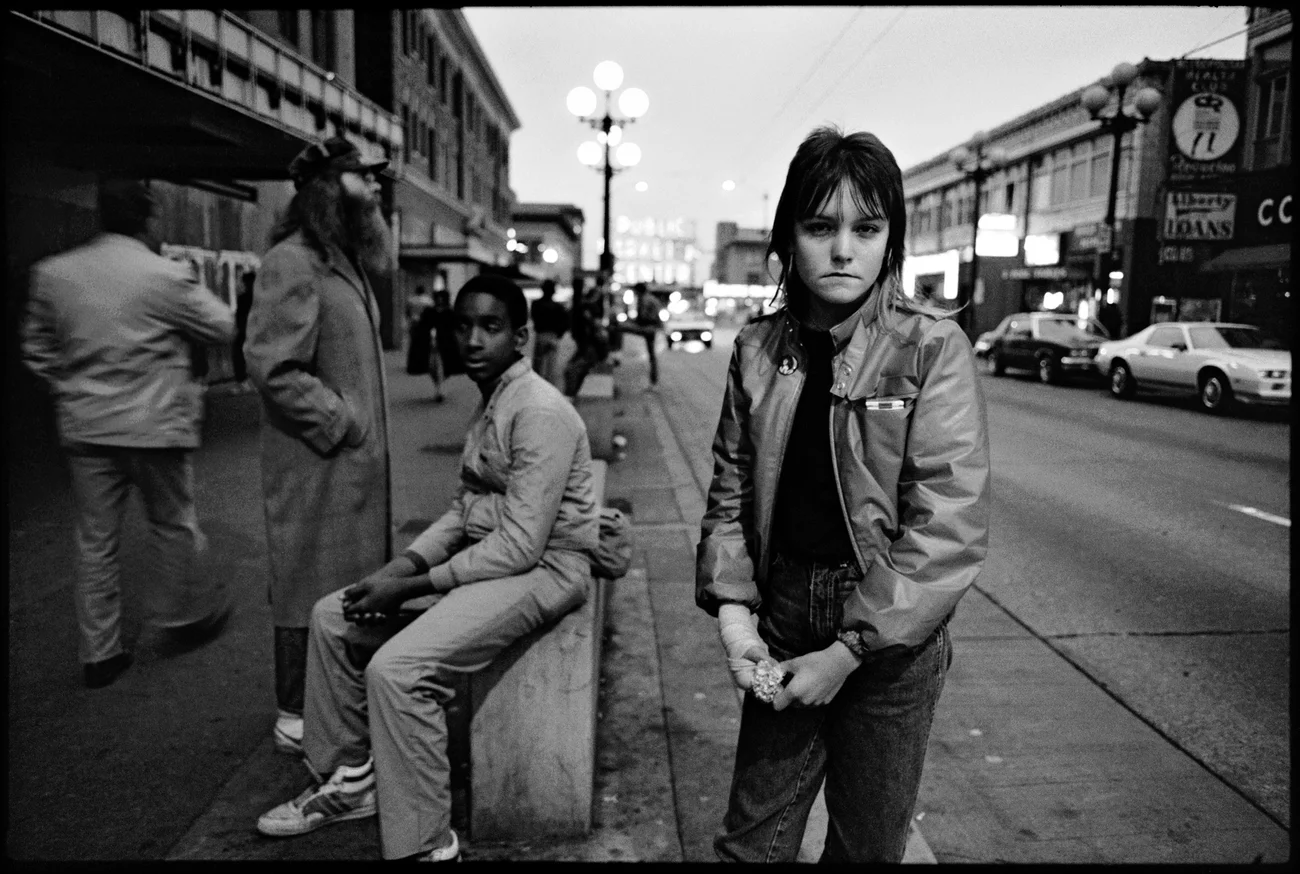

At the heart of Mark’s oeuvre is an ethics of sustained encounter. Her relationship with Tiny—first photographed as a 13-year-old sex worker in Streetwise (1983), then followed across decades into adulthood and motherhood—demonstrates this rare commitment. The photographs are not case studies but chapters of an unfolding biography, as much about survival as decline, as much about resilience as precarity. In this, Mark echoes the long durée of August Sander’s typologies, yet replaces classification with care.

Teaching reinforced this ethos. Students were instructed to spend entire days without cameras, to observe light patterns, to understand what drew them to a subject before lifting the lens. Critiques extended beyond composition to questions of responsibility: who benefits from this image, and at what cost? For Mark, photography was never the endpoint but the residue of a deeper process of listening, waiting, and reciprocating.

Themes as Worlds

Her projects can be read as an atlas of late modern humanity’s margins:

- Institutions (Ward 81): where architecture disciplines but also shelters.

- Sex Work (Falkland Road): where color and spectacle veil both violence and resilience.

- Childhood on the Edge (Streetwise): where innocence collides with survival economies.

- Performance (Indian Circus, Twins): where identity becomes both mask and mirror.

Each body of work oscillates between the micro—the texture of a curtain, the fatigue in a child’s eyes—and the macro—the social systems of neglect, labor, or spectacle. Her photographs are never only about individuals; they are about the worlds those individuals inhabit, worlds often invisible until she rendered them legible.

Legacy and Prophecy

In an era where photography risks dissolving into instant imagery and viral consumption, Mark’s work endures precisely because it resists speed. She reminds us that a photograph is not an act of taking but of giving time: to subjects, to context, to ethics. Like Walter Benjamin’s “aura,” her images retain a charge that cannot be replicated in the scroll of digital feeds. They are slow documents in a fast age.

What remains absent in her archive is also telling: the ease of detachment, the safety of distance. Instead, we inherit images dense with responsibility, haunted by lives that persist beyond the frame. Mary Ellen Mark’s legacy is less a set of pictures than a philosophy — that art and ethics, vision and responsibility, must remain inseparable.

Work Cited

Ideas and work that informed my thinking on this topic:

More Observations on Practice

-

Sage Sohier: Human Connection and Social Relationships

Sohier‘s photography represents a masterful exploration of human relationships, identity, and social dynamics in American life.

-

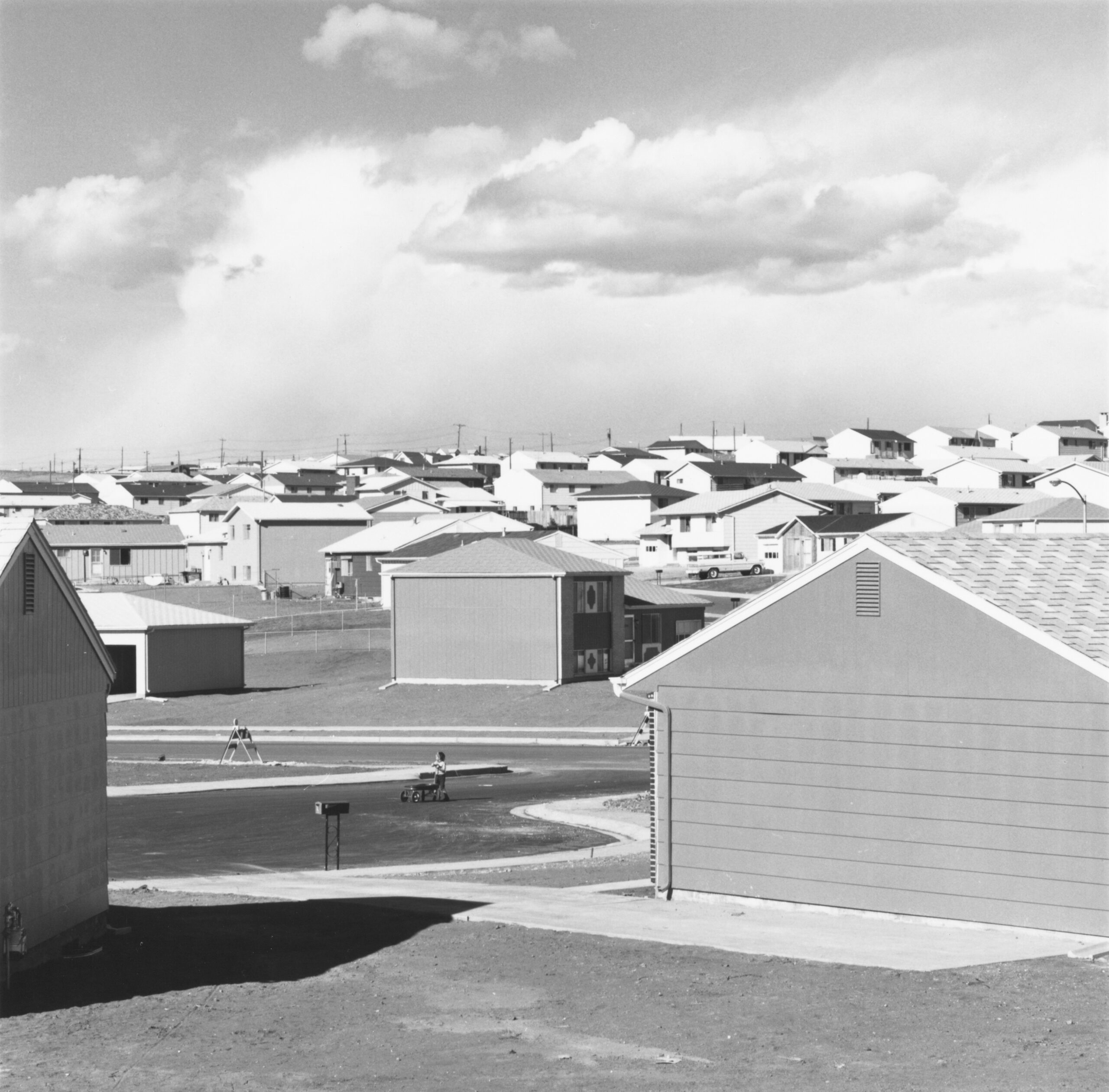

Robert Adams: 15 Observations on Photographing the American West

Robert Adams’ photography stands as one of the most significant documentations of environmental change in the American West.

-

Henri Cartier-Bresson: The Art of Capturing Life’s Fleeting Moments

Henri Cartier-Bresson’s photography captures life’s fleeting moments, revealing depth in everyday scenes.