Double Exposure: How Kyoto and I Became Each Other’s Props

How mass tourism and social media create Baudrillard’s hyperreality.

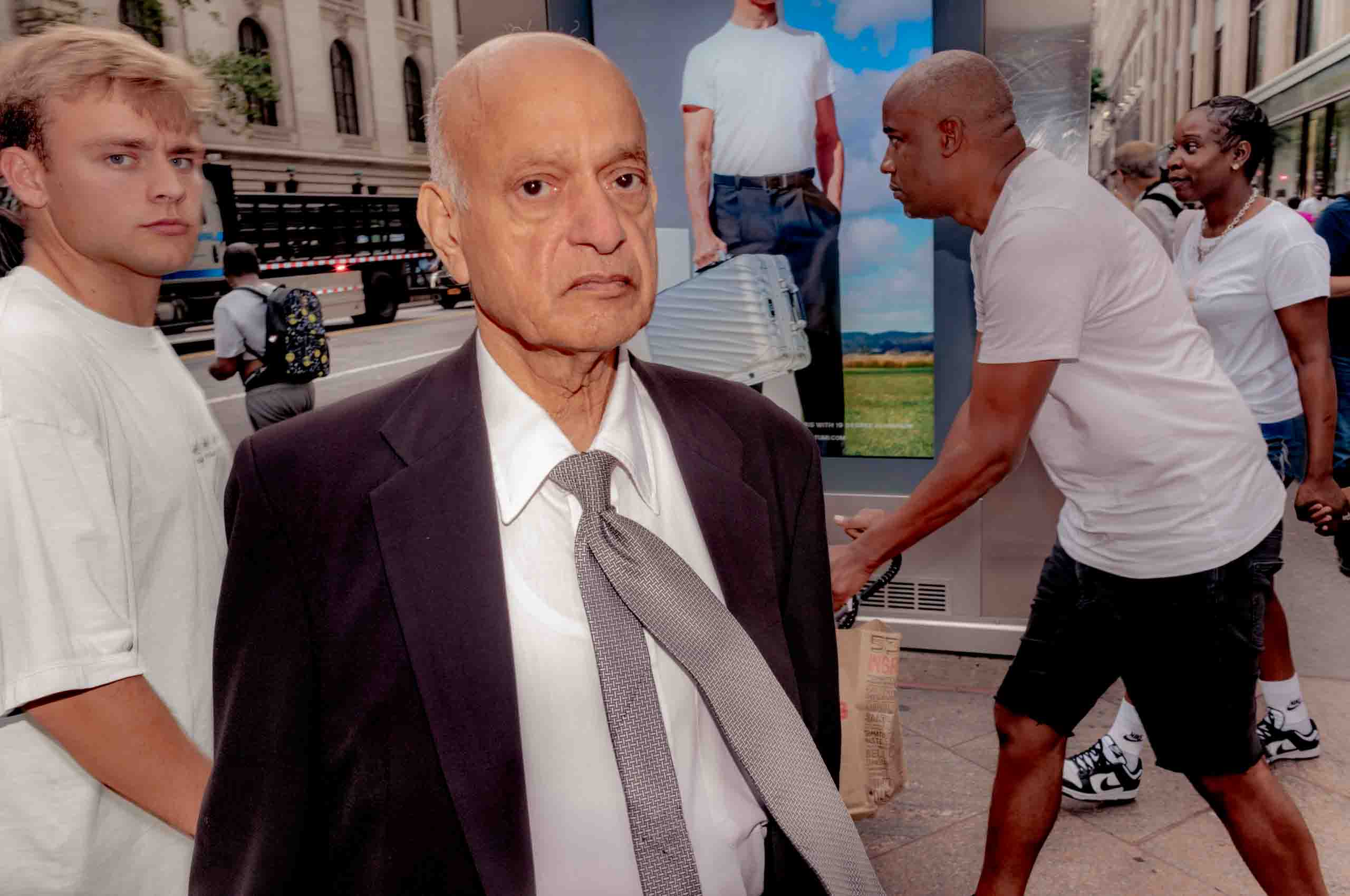

Kyoto is a hall of mirrors. I walk its streets with my camera, watching tourists — myself among them — lift smartphones like votive offerings in prayer. Beneath the vermilion torii gates they pose in gestures rehearsed by algorithms. A Meiko glides past, or perhaps it is a Chinese tourist dressed as one. On my first visit I couldn’t tell the difference. She is real and she is not. This is a place where ritual is ritualized. Where the act of seeing is eclipsed by the compulsion to be seen.

The Performance of Respect

For centuries, Kyoto has been keeper of Japan’s collective unconscious — a living archive of imperial ghosts and Zen paradoxes. Now it tends to another hunger. Shops sell “ancient” sweets wrapped in hashtags. The city performs itself for a global audience that mistakes consumption for communion. Every laneway, every maple-lined path, has become a stage in capitalism’s theater.

Baudrillard called this the “ecstasy of communication” — a world where images detach from meaning and multiply like summer insects at dusk. But what of the ghosts we project onto those images? As a photographer, I’ve come to recognize the shadow in our collective scroll. We flock to Kyoto, not for its reality but for the archetype it sells: “Old Japan” as a mirrored pool in which we glimpse our longing for the sacred. The pool is now glass, and we are too busy photographing our reflections to notice.

This is the paradox of my street practice in Kyoto. When I frame a British couple in rented kimonos, their accents echoing off a thirteenth-century wall, I wonder whether I am documenting an authentic moment or contributing to the feedback loop. My shutter clicks. I know it’s the latter — but press it anyway. Kyoto, ever-compliant, sands down its edges to fit the next story. There is no original left to betray, only a city that survives by vanishing.

What does it mean to photograph a place that photographs back? To wander a labyrinth where every exit leads deeper into the maze of mirrors? Perhaps this is the pilgrimage our age demands: not toward truth, but into the lie we’ve agreed to call beautiful.

Cultural Costume and Commodification

In Kyoto’s costume-tourism economy, the kimono no longer references tradition — it replaces it. These rented garments eIn Kyoto’s costume-tourism economy, the kimono no longer references tradition — it replaces it. These rented garments exist in Baudrillard’s third order of simulacra: copies without originals, where the tourist’s pose becomes the ritual. The fifteen-minute tea ceremony is not a degraded version of the real; it is the real, engineered to satisfy nostalgia for a Japan that never existed outside film and guidebook.

What’s being sold is not cultural appropriation but something subtler — the distorted thrill of self-exoticization.

The tourist paying ¥5000 to wear a machine-washed polyester obi (once reserved for corpses) doesn’t want to be Japanese; they want to perform “Japan” as mediated through anime and Instagram aesthetics. The local shops oblige, stripping symbols of context: the kimono’s left-over-right fold becomes another customizable option.ost pushes the symbol further from its meaning until the kimono signifies nothing but its own photogenic surface.

These images circulating online do not record cultural exchange. They are empty signifiers in a global feedback loop. Each #KyotoVibes post pushes the symbol further from its meaning until the kimono signifies nothing but its own photogenic surface.

I photograph a woman adjusting her rental sash in a shop window. For a moment she seems contemplative, almost reverent. Then she checks her phone and smiles. The image has validated the act; the ritual is complete. I lower my camera, unsure whether I’ve captured the scene or joined it.

The Ethics of Observation

When I frame a boy perched on Tatsumi Bridge, legs dangling above the water — my lens becomes both judge and accomplice. His rebellion depends on my gaze; my critique depends on his act. The camera, a quiet panopticon, makes us both performers: he, the unwitting rule-breaker; me, the documentarian who completes the staging.

The boy’s casual defiance gains significance only through my witnessing. Without documentation, the act dissolves into Kyoto’s air; with it, the moment enters the attention economy, where innocence and condemnation circulate as two sides of the same coin. We mirror Debord’s spectacle: his thoughtless gesture and my moral framing are scripts in the same cultural theater, feeding the machine with content.

My photograph of his trespass now circulates as moralistic clickbait — liked, shared, and discarded beside the very tourism excesses it critiques. Stripped of context, it becomes another empty signifier in the endless scroll of performative outrage. The boy’s face blurs; the warning fades. What remains is the loop: transgression, condemnation, consumption. Even as I press the shutter, I know — the bridge was never the point. The spectacle is.

Sacred Spaces and the Observer’s Paradox

My own images, however critical, feed that system. Awareness doesn’t absolve complicity; it clarifies its terms. The position of the observer, especially one holding a camera, remains a contradiction — trapped between distance and participation, witness and actor. Each frame exposes not purity of vision but the impossibility of innocence.

Kyoto’s shrines now serve two altars: one for prayer, another for poses. The same coins tossed at Fushimi Inari are later gathered, cleaned, and recirculated — a small economy of faith sustaining an industry of images. At Kinkaku-ji, gold leaf once meant to symbolize purity now functions as a natural ring light.

The paradox is everywhere. The more devoutly visitors perform authenticity — hands clasped before Buddhas while adjusting composition — the more the sacred turns to simulation. Even transgressions follow choreography. At Ryōan-ji, the forbidden zones have worn paths where no signs are needed. The most truly sacred spaces may now be those that ban photography altogether. Their refusal feels radical, not for preserving tradition but for resisting circulation.

Respect decays by degrees. Visitors who arrive whispering and barefoot soon speak louder, stand closer, linger longer. The entrance fee implies ownership; reverence shifts quietly to entitlement. Each small trespass — one step too near an altar, one more photograph in a restricted corner — adds to a slow erosion of meaning. Preservation, too, alters what it protects. Rope barriers, guided routes, timed tickets — each safeguard transforms the experience it seeks to defend. What remains is not original sanctity but a curated version of it, devotion managed for display.

To photograph tourists photographing culture is to join the ritual one hopes to analyze. Even critical observation participates in the system it seeks to critique. The camera, feigning neutrality, becomes the engine of hyperreality: it alters behavior, encourages performance, and confirms the illusion of authenticity it claims merely to record.

From Respect to Entitlement

The transformation from respectful observer to entitled actor rarely announces itself. It happens in small, almost invisible shifts. At first, tourists approach temples with genuine reverence — shoes removed, voices lowered, bodies keeping their distance from the sacred. Gradually, the quiet gives way to impulse. The camera comes out. Boundaries loosen. Awe turns to familiarity. Familiarity to ownership.

This passage from respect to presumption mirrors the logic of cultural tourism itself. The act of paying an entrance fee — of purchasing access to sanctity — quietly alters the moral contract. What was once invitation becomes transaction. In the visitor’s mind, the temple becomes a venue, the sacred a backdrop.

The commodification of experience carries its own entropy. When every space is rendered as a potential photograph, what remains of the space itself? Reverence gives way to documentation; the desire to witness becomes indistinguishable from the urge to possess.

The Accumulation of Small Violations

The degradation of cultural boundaries rarely arrives as scandal. It gathers quietly, through an accumulation of minor trespasses — each so small it seems harmless on its own. “Just one photo” on a forbidden bridge. “Just a quick pose” in a restricted corridor. Multiplied across thousands of visitors, these gestures become a slow erosion of authenticity, a wearing down of meaning disguised as curiosity.

The same scene repeats itself everywhere. The infrastructure of tourism — guided tours, rope barriers, designated photo zones — preserves and alters in the same motion. Each attempt to protect the sacred makes it more legible to outsiders, more manageable, more exposed. Every small violation, while trivial in isolation, participates in a larger transformation: the steady conversion of devotion into spectacle.

The cumulative effect is harder to name. At what point does preservation become performance? When does accessibility begin to hollow out the very experience it promises to sustain? These questions hang unanswered, as the crowd moves on to the next site.

Performing “Authentic” Japan

The tourist’s performance of imagined Japanese authenticity exposes the assumptions that underlie cultural desire. Most revealing are the moments when visitors act out what they believe to be “real” Japan — an authenticity assembled from media fragments and industry simplifications. The kimonos, the exaggerated bows, the peace signs before temple gates — these gestures express not curiosity but possession, the wish to hold a culture by performing it.

These performances capture not Japan but outsider fantasies of it, revealing more about the visitors’ imagination than about Japanese tradition.

The tourism industry, fluent in this fantasy, provides the settings and scripts. The result is a form of cultural cosplay that dissolves the boundary between appreciation and appropriation. When rituals become photo opportunities, when reverence is scheduled and sold, meaning drains quietly away.

Authenticity itself becomes suspect. Is there an “authentic” way for outsiders to experience another culture, or does the pursuit of authenticity guarantee its distortion?

Like Baudrillard’s Disneyland, these rituals exist to persuade us that somewhere beyond the performance, the real still exists.

Yet the more carefully we stage respect — the deeper the bow, the quieter the whisper — the more visible the artifice becomes.

The Impossibility of Innocent Observation

The concept of innocent observation dissolves under scrutiny, revealing complex networks of influence and impact. Every tourist, camera or not, alters the spaces they move through and the cultures they attempt to witness. Photography doesn’t simply document reality — it creates new realities through the act of documentation.

This transformation takes place on multiple levels. The physical presence of tourists changes how sacred spaces function. The act of photography alters how these spaces are perceived and used. And the circulation of images shapes expectations for future visitors. The cumulative effect extends beyond individual moments of documentation. It influences how cultures present themselves to the outside world.

This process of mutual transformation — where both observer and observed are changed by the act of observation — raises questions about cultural preservation in an age of mass tourism. The act of trying to preserve traditional cultures through documentation may accelerate their transformation into something new.

The Ethics of Cultural Tourism Beyond Simple Binaries

The exchanges between tourists and sacred spaces in Kyoto resist easy moral sorting. Appreciation and appropriation are not opposites. They are points on a continuum shaped by power, economy, and desire. Traditional ethics falter here because they can’t contain a system where social media, global capitalism, and local custom fuse into hybrid forms of cultural practice.

The commodification of sacred sites depends on both visitors and residents. Temple administrators balance preservation with accessibility, ritual with revenue. Their compromises reveal how tourism operates within global systems of exchange, where the wish to experience authenticity inevitably changes what is experienced. The question now isn’t how to prevent change but how to manage it without erasing the meaning that drew us here in the first place.

Conclusion: Navigating Cultural Boundaries in an Age of Global Tourism

Kyoto’s sacred spaces reflect tourism’s central paradox: the wish to preserve culture inevitably changes it. Through my lens I’ve watched small transgressions accumulate, performances of “authenticity” harden into ritual, and observation turn quietly into participation. There are no innocent encounters here — my camera, like the tourists’ selfie sticks, alters what it seeks to preserve.

Yet this transformation isn’t simple ruin. It produces new cultural hybrids, shaped by the tension between devotion and display. The task — for photographers and visitors alike — is to move through these spaces with a clear awareness of consequence.

My photographs offer no solution, only evidence of complicity.

Perhaps that awareness is the closest we come to ethics: knowing that every act of witnessing leaves a trace, and accepting that the trace is ours.

Work Cited

Ideas and work that informed my thinking on this topic:

More Field Notes and Visual Culture & Theory

-

Why I Reject the Pretense of Documentary Neutrality

Neutrality is a myth. Every photograph is already a construction. It’s a comforting illusion to think otherwise.

-

Cindy Sherman’s Deepfake Ghost: Performing Identity

Cindy Sherman’s groundbreaking self-portraits expose identity as a constructed performance.