The City as Living Archive

The city, as I read it, is a living archive—messy, polyphonic, and resistant to closure.

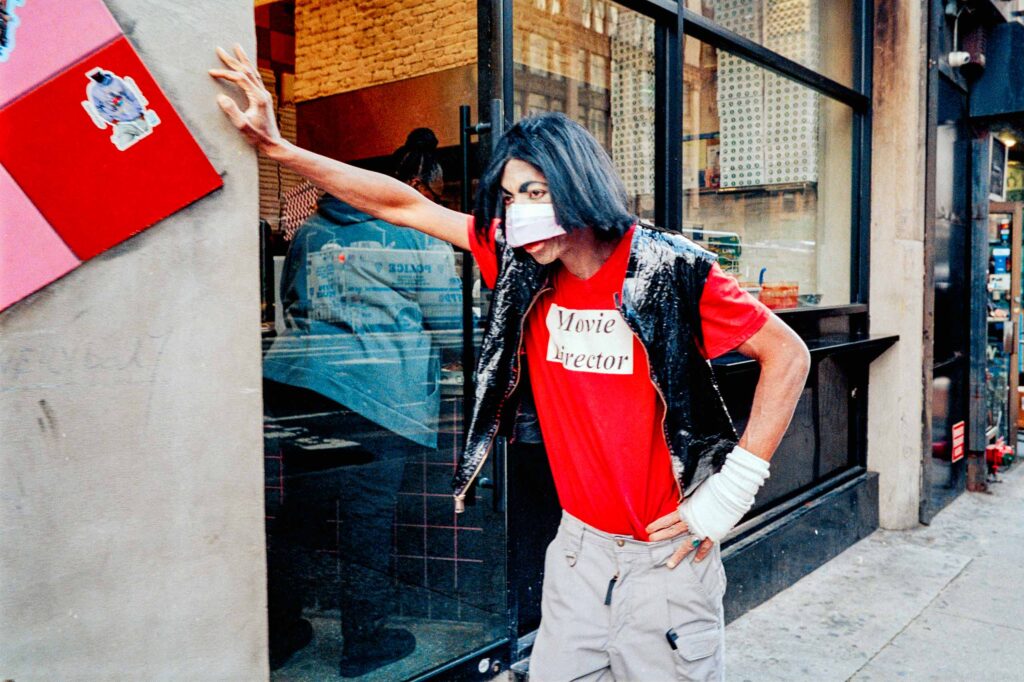

The city speaks in fragments. I’ve come to see it as a living archive, not just some static backdrop, In the city, every surface, person, and gesture carries traces of past lives, fleeting desires, and unspoken social rules and codes. To walk with a camera feels like reading that archive in motion. I notice how small acts like someone pausing on a corner, glancing at an advertisement, what their body language reveals about their inner state — all of this collides with broader social forces. Street photography (for me at least) has become less so about capturing any facts or truths, and more about entering a dialogue between myself, the people I encounter, and the city itself. The conversation continues long after the shutter clicks.

Camera as Collaborator

The camera isn’t neutral. It mediates my relationship with the city. Roland Barthes wrote about the photograph’s “that-has-been,” its link to reality. But framing, timing, and intent complicate that idea. What the camera shows is always a fragment, carefully chosen. Lacan’s theory of the gaze makes sense here: photography is a confrontation between what’s visible and what’s hidden, between desire and absence. When I lift the camera, I’m not just looking. I’m participating. I’m shaping what appears.

Often, this happens in hesitation. On a crowded corner, I sometimes notice how I feel this tension between impulse and restraint. Should I press the shutter now, or wait? Every choice is technical and also instinctual, informed by my own projections and the unspoken social rules around me. These small negotiations remind me that meaning is never fixed. It emerges in the space between photographer and subject.

The City as Text

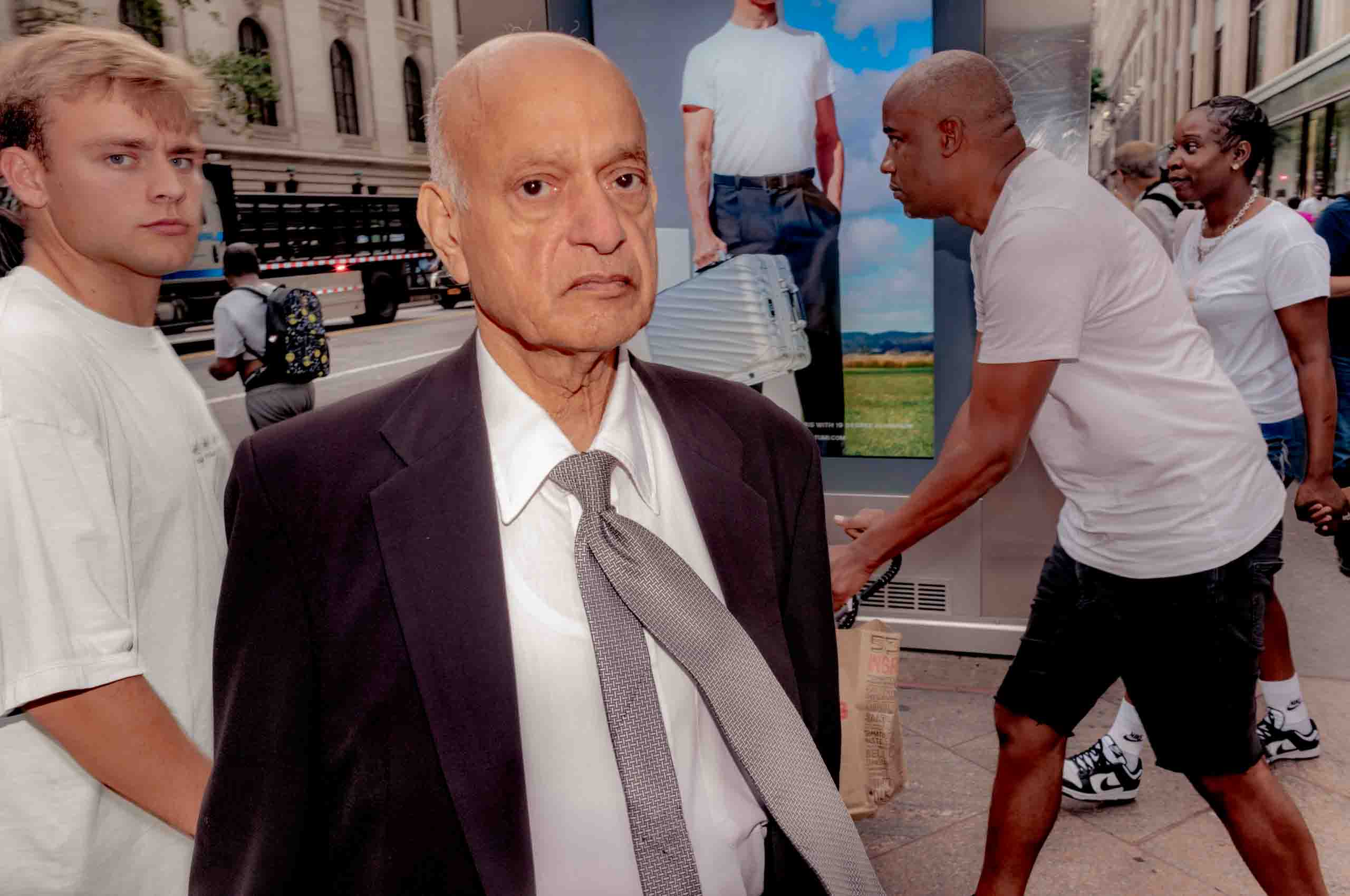

I remember one instance in particular, on 42nd and 5th, a popular Manhattan intersection for many New York City street photographers because of its proximity to Grand Central Station and other midtown landmarks. A man paused in front of me with a cigarette hanging from his lips. His eyes were fixed on a coin in his open hand. The city around him moved. Families, tourists, office workers, street vendors. What struck me and perhaps triggered my impulse to press the shutter was how absorbed he was in that small but private decision.

Looking at this picture now, I notice how that moment suspended crystalizes so many tensions. Youth and precarity, wealth and survival, individuality and anonymity. The coin is both ordinary and symbolic. Chance, value, fate. In the city’s archive, he’s a figure of decision under pressure. His gesture was fleeting and unposed and it read to me like a pause in the relentless grammar of movement that defines so much of our public space.

The city around him moved—families, tourists, office workers, street vendors. What struck me was how absorbed he was in that small, private decision. That moment suspended so many tensions. Youth and precarity, wealth and survival, individuality and anonymity. The coin is both ordinary and symbolic: chance, value, fate. In the city’s archive, he’s a figure of decision under pressure. His gesture, fleeting and unposed, reads like a pause in the relentless grammar of movement that defines our public space.

Hidden Currents

Psychoanalysis helps me think about why street photography matters. Freud saw dreams as condensed desire; Jung saw them as echoes of the personal and collective unconscious. The city stages unconscious desire in public form. Advertising, shop windows, strangers brushing past each other—all carry symbolic weight. When I photograph, I often sense I’m capturing more than surface reality. I’m tapping into the city’s hidden currents.

Lacan’s mirror stage feels relevant: when a child recognizes itself in a reflection. The city works like that mirror. A subject I photograph might reveal as much about my own anxieties as about theirs. The street becomes both social stage and psychic stage. The self-portrait I made last year showed only my shadow on pavement, camera raised. The image held more absence than presence, which felt true to how I move through the city—visible but not quite there.

Between Frame and Viewer

The photograph doesn’t end with the shutter. It lives again when someone sees it. Benjamin called each photograph a “tiny spark of contingency,” capable of igniting new meanings. Viewers bring their own experiences and biases. A gesture I see as tenderness might appear as alienation to someone else. That’s not a flaw. It’s the point. Meaning in photography is never fixed.

This is where documentary and poetry meet. The image captures a trace of reality, but its significance is open, unstable, alive. Photographing means accepting that uncertainty, knowing the city isn’t a closed text but an unfinished one.

What the Practice Reveals

My attraction to street photography has less to do with capturing “reality” and more to do with learning to listen — to the city, to strangers, and to my own subconscious responses. The camera is the perfect companion because it sharpens my attention. It allows me to notice gestures or alignments I might otherwise overlook. It also reminds me that neutrality is impossible. Every frame shapes the archive; it doesn’t simply record it.

I revisit neighborhoods to feel how they change over time. The archive I build is both visual and emotional—a record of moods, silences, half-finished encounters. My photographs ask questions more than they answer: How do people navigate public codes? Where do desire and regulation collide? What does it mean to see, and to be seen, in this city?

The man with the coin appears in my archive as a question I couldn’t answer. Did he flip it? Which way did he walk? I’ll never know. I moved on before the moment resolved. Street photography trades in these incompletions. The city offers them endlessly. Each photograph is a fragment of dialogue—between me and the street, subject and gaze, image and viewer.

Threshold Work

To walk in the city with a camera is to inhabit a threshold space. It’s a space between the personal and collective. The visible and the invisible. The historical and the fleeting. The city is a messy polyphonic place that is resistant to closure and certainty. My goal isn’t to resolve meaning but to trace it, to hold open the tension between documentation and interpretation.

Every day when I step outside to return to the same corners, the same quality of light. The archive grows. The city ris always rewriting itself. I don’t know if I’m reading the city or if it’s reading me. Perhaps that’s the conversation. Not knowing where observation ends and projection begins. Not where the archive stops documenting and starts revealing.

More Field Notes and Visual Culture & Theory

-

Why I Reject the Pretense of Documentary Neutrality

Neutrality is a myth. Every photograph is already a construction. It’s a comforting illusion to think otherwise.

-

Double Exposure: How Kyoto and I Became Each Other’s Props

How mass tourism and social media create Baudrillard’s hyperreality.

-

Cindy Sherman’s Deepfake Ghost: Performing Identity

Cindy Sherman’s groundbreaking self-portraits expose identity as a constructed performance.