Double Exposure: How Kyoto and I Became Each Other’s Props

How mass tourism and social media create Baudrillard’s hyperreality.

Kyoto is a hall of mirrors. I wander the streets with my camera, watching tourists—all of us tourists—raise smartphones like votive offerings. They pose beneath vermilion tori gates, their gestures rehearsed from social media algorithms. A geisha glides past, or is it a Chinese tourist cosplaying one? I can recognize the difference now, but didn’t on my first visit. She is real, and she is not. This is a place where ritual becomes ritualized, where the act of seeing is eclipsed by the compulsion to be seen.

- The Performance of Respect

- Cultural Costume and Commodification

- The Ethics of Observation

- Sacred Spaces as Stages

- From Respect to Entitlement

- The Accumulation of Small Violations

- Performing “Authentic” Japan

- The Observer’s Paradox

- The Impossibility of Innocent Observation

- The Ethics of Cultural Tourism Beyond Simple Binaries

- Conclusion: Navigating Cultural Boundaries in an Age of Global Tourism

- Further Reading

For centuries, Kyoto has been the keeper of Japan’s collective unconscious—a living archive of imperial ghosts and Zen paradoxes. Now it caters to a different kind of hunger. Shops sell “ancient” sweets wrapped in hashtags. The city no longer is. It performs, endlessly, for an audience that mistakes consumption for communion. Every laneway, every maple-lined path, has become a stage in capitalism’s theater.

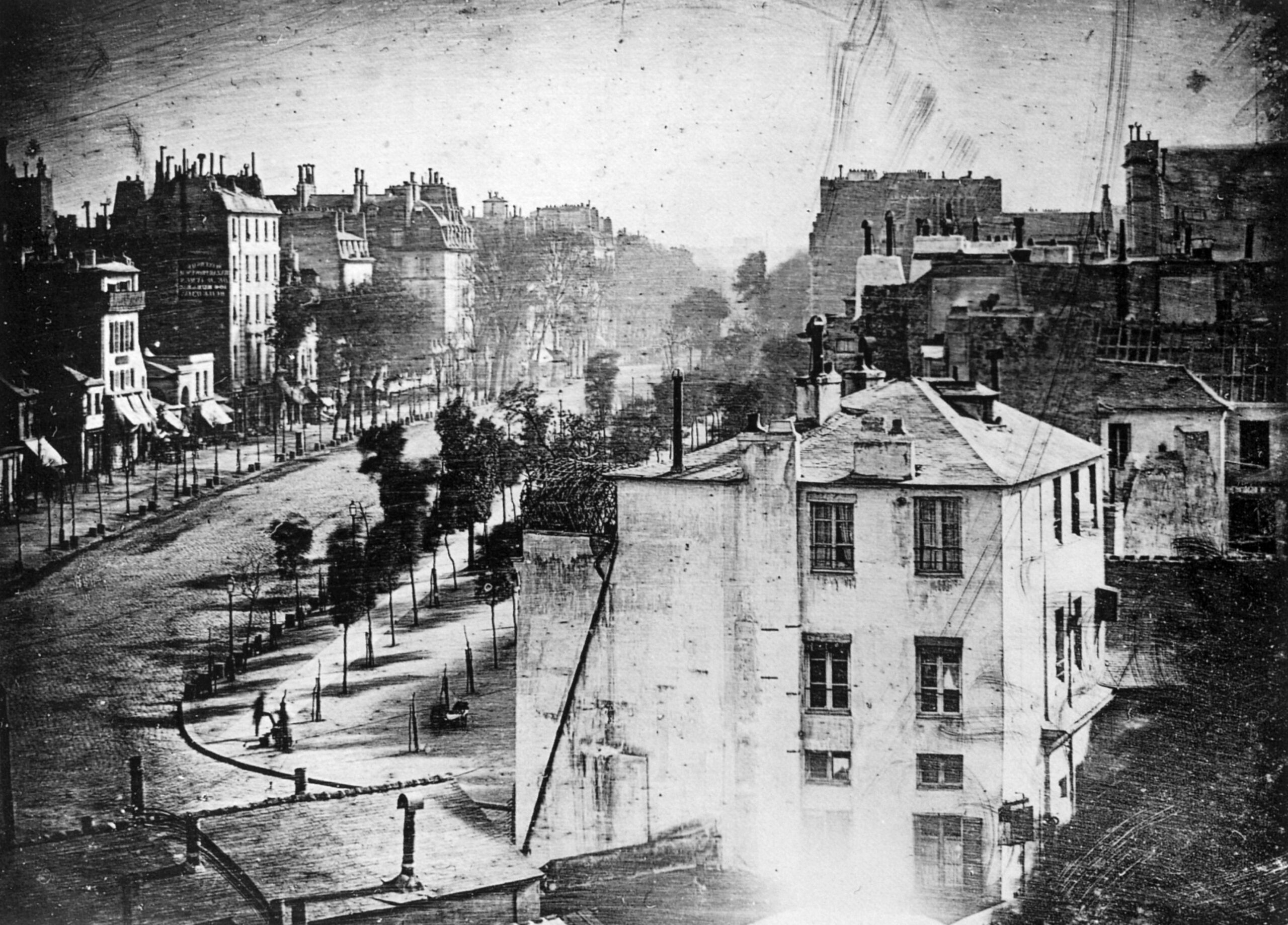

Baudrillard called this the “ecstasy of communication”—a world where images detach from meaning and swarm like spotted lanternflies in a New York summer. But what of the ghosts we project onto these images? As a photographer, I’ve come to recognize the shadow lurking in our collective scroll. We flock to Kyoto not for its reality, but for the archetype it sells: “Old Japan” as a mirrored pool where we glimpse our longing for the sacred. The problem is, the pool is now glass, and we’re too busy taking selfies to notice we’re reflections ourselves.

This is the paradox of my street practice in Kyoto. When I frame a British couple in rented kimonos, their accents echoing off a 13th-century wall, I wonder if I am documenting an authentic moment or adding to the endless feedback loop. My shutter clicks. I know it’s probably the latter—but press it anyway. Kyoto, ever-complicit, sands down its edges to fit the next story. There is no original left to betray, only a city that survives by vanishing.

What does it mean to photograph a place that photographs back? To wander a labyrinth where every exit leads deeper into the maze of mirrors? Perhaps this is the pilgrimage our age demands: not toward truth, but into the lie we’ve agreed to call beautiful.

Jean Baudrillard (1929–2007) was a French philosopher, sociologist, and cultural theorist whose work is central to understanding postmodernity. He argued that in late capitalist societies, the boundary between reality and representation collapses. What remains is the hyperreal: a condition where simulations (images, symbols, and staged experiences) replace any original meaning, becoming more “real” than reality itself.

The Performance of Respect

In Kyoto’s costume tourism economy, the kimono no longer references tradition—it replaces it. These rented garments exist in Baudrillard’s third order of simulacra: copies without originals, where the tourist’s Instagram pose becomes the ritual. The tea ceremony’s 15-minute “experience” isn’t a degraded version of the real; it is the real, meticulously engineered to satisfy our nostalgia for a Japan that never existed outside of films and guidebooks.

What’s being sold isn’t cultural appropriation, but something more postmodern: the ecstasy of self-exoticization.

The tourist paying ¥5000 to wear a machine-washed polyester obi (traditionally reserved for corpses) doesn’t want to be Japanese—they want to perform “Japan” as mediated through anime and Instagram aesthetics. The local shops oblige by stripping symbols of all context: the kimono’s left-over-right folding now just another customizable option.

These images circulating on social media don’t document cultural exchange—they’re empty signifiers in a global feedback loop. Each #KyotoVibes post further divorces the symbol from its meaning, until the kimono signifies nothing but its own photogenicity.

Cultural Costume and Commodification

In Kyoto’s costume tourism economy, the kimono no longer references tradition—it replaces it.

These rented garments exist in Baudrillard‘s third order of simulacra: copies without originals, where the tourist’s Instagram pose becomes the ritual. The tea ceremony’s 15-minute “experience” isn’t a degraded version of the real; it is the real, meticulously engineered to satisfy our nostalgia for a Japan that never existed outside of films and guidebooks.

What’s being sold isn’t cultural appropriation, but something more postmodern: the ecstasy of self-exoticization.

The tourist paying ¥5000 to wear a machine-washed polyester “obi” doesn’t want to be Japanese—they want to perform “Japan” as mediated through anime and Instagram aesthetics. The local shops oblige by stripping symbols of all context: the kimono’s left-over-right folding (reserved for corpses) now just another customizable option.

These images circulating on social media don’t document cultural exchange—they’re empty signifiers in a global feedback loop. Each #KyotoVibes post further divorces the symbol from its meaning, until the kimono signifies nothing but its own photogenicity.

The Ethics of Observation

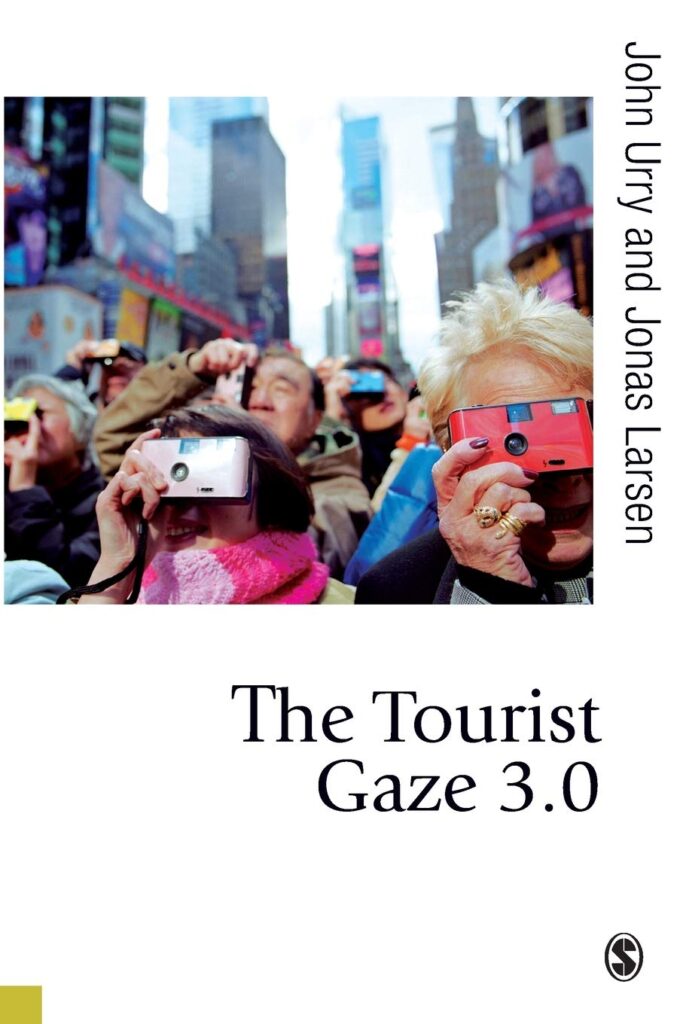

Of course, I’m aware that with every press of my shutter, I am trapped in a Foucauldian paradox: the observer who documents transgression cannot escape being part of the spectacle. And yet, I can’t help myself.

When I frame a boy perched on the bridge—defiant against the “Don’t sit on the bridge” sign—my lens becomes both judge and accomplice. His rebellion is incomplete without my gaze, just as my critique is meaningless without his act. The camera, a postmodern panopticon, turns us both into performers: him, the unwitting rule-breaker; me, the documentarian complicit in his staging.

Consider the viral calculus at work here. The boy’s careless posture—legs dangling over the railing—gains its power only through my witnessing. Without documentation, his transgression evaporates into the Kyoto air, unremarkable. But captured, it enters the attention economy, where his innocence and my censure become two sides of the same coin. We mirror Debord’s spectacle: his thoughtless act and my moralizing frame are just different scripts in the same cultural theater, feeding the machine with content.

The cruel irony? My photograph of his trespass now circulates as moralistic clickbait—liked, shared, and discarded alongside the very tourism excesses it critiques. The image, stripped of context, becomes an empty signifier in the endless scroll of performative outrage. The boy’s face blurs; the sign’s warning fades. All that remains is the loop: transgression, condemnation, consumption. Even as I press the shutter, I know—the bridge was never the point. The spectacle is.

Sacred Spaces as Stages

Kyoto’s shrines now serve dual altars: one for prayers, another for poses. The same coins tossed at Fushimi Inari are later collected, cleaned, and recirculated—spiritual economy feeding the Instagram machine. At Kinkaku-ji, gold leaf meant to symbolize purity now primarily functions as nature’s ring light.

We’ve created a paradox: the more devoutly visitors perform “authentic” experiences (hands clasped before Buddhas while checking their screen’s composition), the more the sacred becomes simulation. Even transgressions follow scripts—the most photographed “forbidden” zones at Ryoan-ji have worn paths where no signage exists.

Theological irony: the most authentically sacred spaces in Kyoto may now be the few that ban photography entirely—not because they preserve tradition, but because their emptiness of images makes them radical exceptions in an economy of visual consumption.

From Respect to Entitlement

The transformation from respectful observer to entitled actor often occurs in subtle, almost imperceptible stages. This shift reveals much about the nature of cultural tourism and its impact on both visitors and sites. Tourists who begin their temple visits with genuine reverence—removing shoes, speaking in whispers, maintaining appropriate distance from sacred objects—may gradually adopt more invasive behaviors as their initial awe fades.

This transition from respect to familiarity to entitlement often happens unconsciously, reflecting a broader pattern in how tourists consume cultural spaces. The very act of paying an entrance fee can create a sense of ownership, transforming sacred spaces into commercial venues in the visitor’s mind.

This commodification of experience raises questions about the sustainability of cultural tourism itself. When every space becomes a potential photo opportunity, what remains of its original spiritual or cultural significance? The camera becomes both witness to and catalyst for this transformation, documenting the moment when appreciation turns to appropriation.

The Accumulation of Small Violations

The gradual degradation of cultural boundaries occurs not through dramatic transgressions but through an accumulation of minor violations, each seemingly insignificant in isolation. “Just one photo” on a forbidden bridge, “just a quick pose” in a restricted area—these small acts of defiance, multiplied across thousands of daily visitors, contribute to a slow erosion of cultural authenticity.

This process reveals the challenge of preserving sacred spaces in an age of mass tourism. The infrastructure of tourism—from guided tours to protective barriers—simultaneously preserves and alters these sites. Each small transgression, while perhaps harmless in itself, contributes to a larger pattern of cultural transformation.

The collective impact of these minor violations raises questions about responsibility and preservation. When does preservation become preservation in name only? At what point does accessibility compromise the very essence of what visitors come to experience?

Performing “Authentic” Japan

The tourist’s performance of imagined Japanese authenticity reveals deeply embedded assumptions about cultural experience and ownership. Most revealing are the moments when visitors enact what they believe to be authentic Japanese culture – an authenticity often constructed from media representations and tourist industry simplifications. The proliferation of kimono photoshoots, exaggerated bows, and peace signs in front of temples speaks to a deeper desire not just to witness but to somehow possess the culture being observed.

These performances capture not Japan, but outsider fantasies about Japan, revealing more about the visitors’ cultural imagination than about Japanese tradition itself.

The tourism industry actively facilitates these performances, creating spaces and opportunities for cultural cosplay that blur the line between appreciation and appropriation. This commercialized version of cultural experience raises questions about authenticity in an age of global tourism. When traditional practices become photo opportunities, when sacred rituals transform into tourist experiences, what remains of their original meaning?

The very concept of authenticity becomes problematic – is there an “authentic” way for outsiders to experience another culture, or does the desire for authenticity itself create an impossible standard?

Like Baudrillard’s Disneyland, these rituals exist to convince us that somewhere outside the performance, “real” Japan still exists.

But the more meticulously we stage respect (the deeper the bow, the quieter the whisper), the more obvious the artifice becomes.

The Observer’s Paradox

The position of the cultural observer, particularly one armed with a camera, exists in a state of perpetual contradiction. Even critical observation participates in the system of cultural consumption it seeks to analyze. This paradox extends beyond simple documentation to question the very possibility of neutral observation. The act of photographing tourists photographing culture creates layers of removal from direct experience, yet each layer reveals new aspects of how cultural tourism functions.

The observer’s attempt to maintain critical distance while remaining engaged in the phenomenon under study mirrors larger questions about cultural tourism itself. Can we truly observe and document cultural practices without affecting them? The camera’s presence alters behavior, creates self-consciousness, and potentially encourages the very performances it seeks to critique. This awareness of the observer’s role in shaping what is observed connects to broader questions about representation and power in cultural documentation.

The Impossibility of Innocent Observation

The concept of innocent observation dissolves under scrutiny, revealing complex networks of influence and impact. Every tourist, whether wielding a camera or not, alters the spaces they move through and the cultures they attempt to witness. As Barthes suggested, photography doesn’t simply document reality – it creates new realities through the act of documentation.

This transformation occurs on multiple levels: the physical presence of tourists changes how sacred spaces function, the act of photography alters how these spaces are perceived and used, and the circulation of images shapes expectations for future visitors. The cumulative effect extends beyond individual moments of documentation to influence how cultures present themselves to the outside world.

This process of mutual transformation – where both observer and observed are changed by the act of observation – raises fundamental questions about cultural preservation in an age of mass tourism. The very act of trying to preserve traditional cultures through documentation may accelerate their transformation into something new and different.

The Ethics of Cultural Tourism Beyond Simple Binaries

The complex interactions between tourists and sacred spaces in Kyoto demand a more nuanced understanding of cultural tourism ethics than simple categories of right and wrong can provide. When does appreciation become appropriation? The answer lies not in specific actions but in the broader context of power relations, economic pressures, and cultural transformation. Traditional frameworks for understanding cultural exchange fail to capture the complexity of modern tourism, where social media, global capitalism, and local tradition create new hybrid forms of cultural practice.

The commodification of sacred spaces occurs with the participation of both visitors and local communities, creating economic dependencies that complicate questions of authenticity and preservation. Temple administrators must balance preservation with accessibility, tradition with financial sustainability. This balancing act reveals how cultural tourism operates within larger systems of global exchange, where the desire to experience “authentic” culture inevitably transforms what is experienced. The question becomes not how to prevent change, but how to manage it in ways that respect both tradition and the inevitable evolution of cultural practices.

When I photograph a tourist pretending to meditate, I’m not documenting sacrilege. I’m documenting a meta-ritual: the performance of “spirituality” for an audience that no longer distinguishes between sacred acts and their aestheticized traces. The camera here isn’t neutral—it’s the engine of hyperreality, transforming lived culture into consumable image. Baudrillard was right: “To simulate is not to feign.” The tourists aren’t lying; they’re operating within a system where all experience is already mediated.

My own photographs, however critical, feed the same machine.

Conclusion: Navigating Cultural Boundaries in an Age of Global Tourism

Kyoto’s sacred spaces hold up a mirror to tourism’s central paradox: our desire to preserve cultures inevitably changes them. Through my lens, I’ve documented how small transgressions accumulate, how performances of “authenticity” reshape traditions, and how even observation becomes participation. There are no innocent encounters here—my camera, like the tourists’ selfie sticks, has altered what it sought to preserve.

Yet this transformation isn’t simple destruction. What emerges are new cultural hybrids, born from the tension between tradition and tourism. The challenge—for photographers and visitors alike—is to approach these spaces with clear-eyed awareness of our impact.

My images offer no solutions, only proof that we’re all complicit.

Perhaps that recognition is the first step toward more ethical engagement: understanding that every act of witnessing leaves its mark. But then again, what is ethical engagement anyway? And more importantly, who decides what it looks like?

Work Cited

Ideas and work that informed my thinking on this topic:

More Field Notes and Visual Culture & Theory

-

The Myth of Objectivity: How Press Photography Manufactures Reality

Reality was never the point. What we actually crave is credibility — the illusion that the world can still be known if we frame it just right.

-

Photography’s Long Battle for Artistic Legitimacy

Photography was born not in studios of painters but in laboratories. The medium’s first practitioners were chemists, astronomers, inventors, and entrepreneurs, tinkering with glass plates and light-sensitive chemicals.