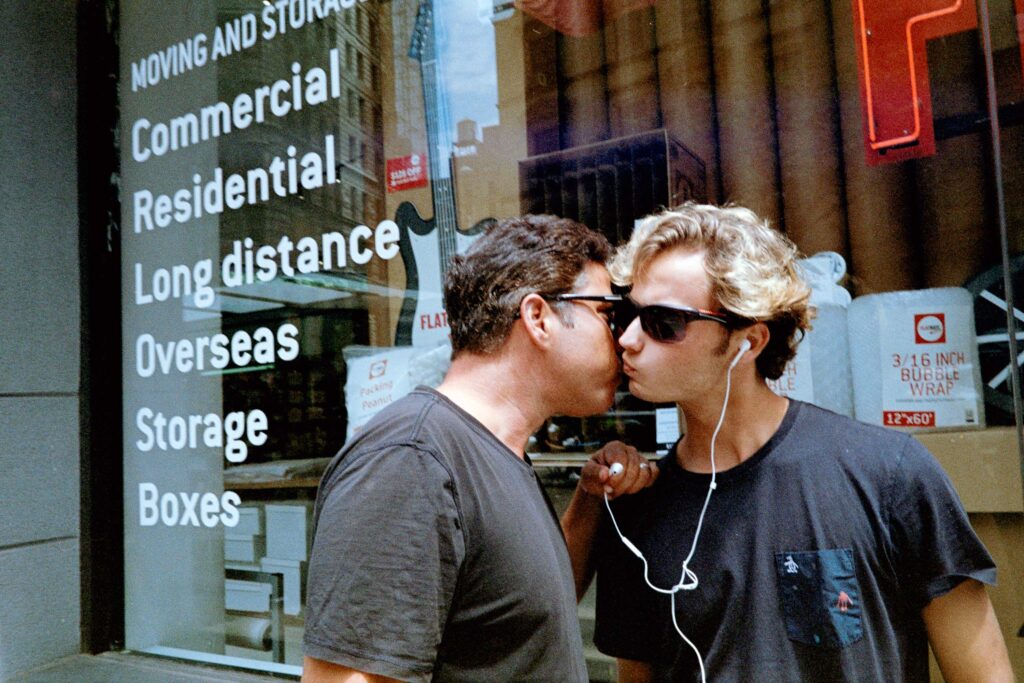

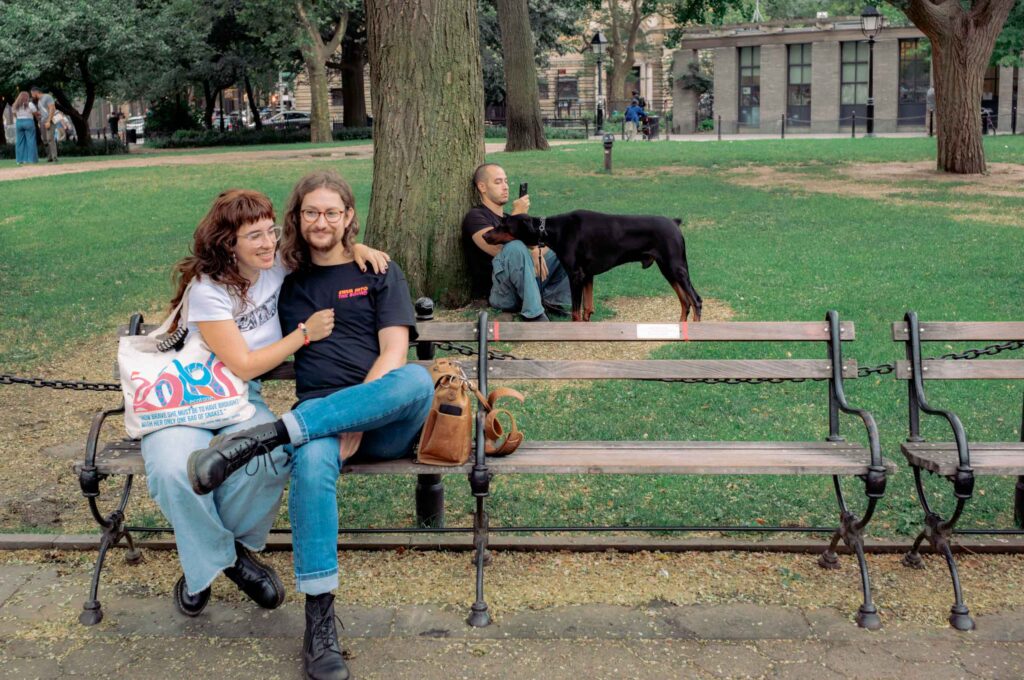

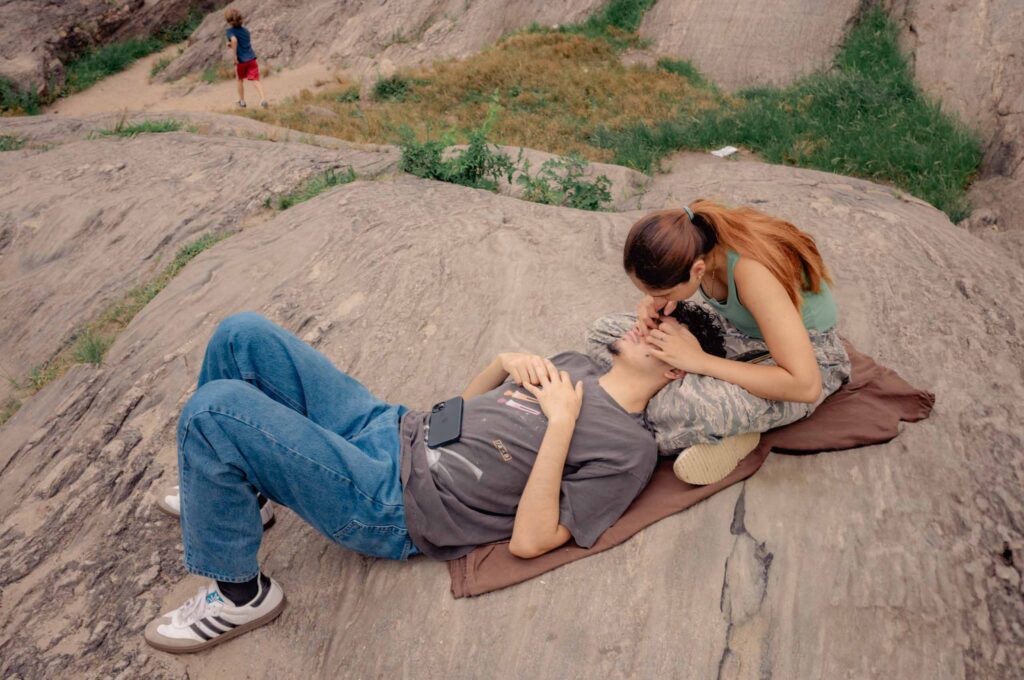

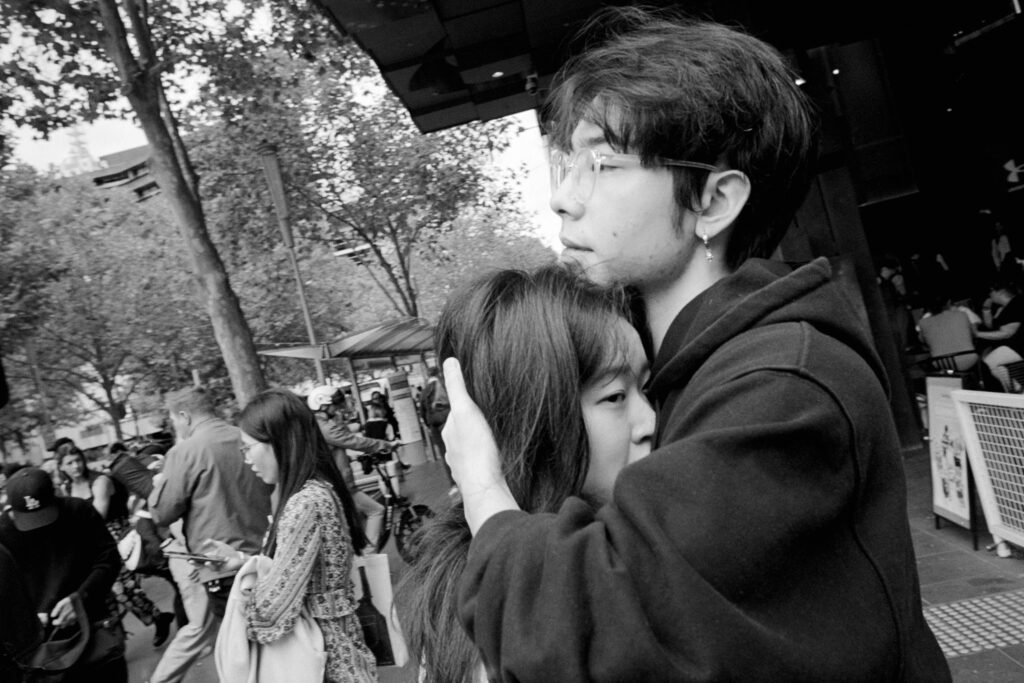

These city images show The Lover archetype at work in urban spaces. Jung saw this force as basic to human nature. It’s not just romance. It’s our pull toward beauty, creativity, and connecting with the world through our senses. His contemporary, Lacan, saw something different. He noticed a structural problem we can’t escape: we don’t fall for the actual person. We chase something called objet petit a—the thing that triggers our desire that we stick onto them. This means we never really get what we want because we think we’re connecting with someone real, but in reality — we’re actually just chasing our own projections.

This archetype opens up the potential for both positive and negative dimensions. Stories from every culture repeat the same patterns. Think of Eros and Psyche’s eternal bond. Or Romeo and Juliet’s passion that killed them both. Love gives us energy and inspiration. It helps us make real connections. But it can also eat us alive. It blurs who we are and makes us lose ourselves. Lacan goes further. He says we don’t love the actual person at all. We love something extra that we’ve put on them. When we love someone, we change who they really are in our minds. We’re chasing ghosts we made ourselves.

Looking at these images, Jung’s hopeful view fights with Lacan’s doubt about real relationships. That look that starts desire isn’t about truly seeing someone. It’s about getting caught by forces we don’t control or understand. We all wear masks. We never know what we represent in someone else’s unconscious story. Tech has evolved, but it seems we’re still driven by the same basic forces that have moved people since we began telling stories. We keep reaching for each other even though we might miss. The Lover stays strong through every cultural change and historical evolution. It adapts, it never goes away.